Linnea Sinclair wrote, Monday April 7th 2008:

---------------

Q - My critique partners tear apart and change everything I write. What am I doing wrong?

A - Possibly nothing. Possibly everything. My first concern is, who are your crit partners? Do they have books on the shelves of Barnes & Noble or Waldenbooks? Have they actively studied the craft of writing? Or are they just starting out, putting pen to paper or fingers to keyboard?

Jack Bickham, a noted writing guru, states in his The 38 Most Common Fiction Writing Mistakes, "Usually it's a mistake to seek advice from other amateurs at writers' clubs. I don't think it's a good idea to ask family or friends to read and 'criticize' your manuscript, either...for two reasons: they won't be honest; they usually don't know what they're doing anyway ...

---------------

A - Possibly nothing. Possibly everything. My first concern is, who are your crit partners? Do they have books on the shelves of Barnes & Noble or Waldenbooks? Have they actively studied the craft of writing? Or are they just starting out, putting pen to paper or fingers to keyboard?

Jack Bickham, a noted writing guru, states in his The 38 Most Common Fiction Writing Mistakes, "Usually it's a mistake to seek advice from other amateurs at writers' clubs. I don't think it's a good idea to ask family or friends to read and 'criticize' your manuscript, either...for two reasons: they won't be honest; they usually don't know what they're doing anyway ...

---------------

This is really a very deep, wide ranging and intricate issue. Where can a new writer get reliable advice?

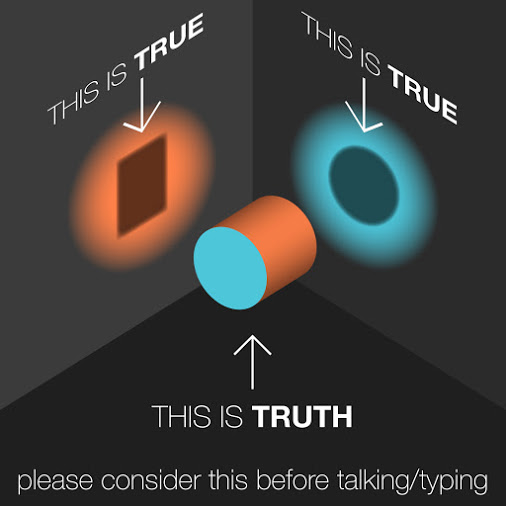

Some people shrug it off as, "Well, it's art, so there is no "wrong." It's all a matter of taste."

And that's true for Art. But it's not true for commercial art.

There is a part of novel writing that actually has that "there is no wrong" aspect to it, but that part can't be learned and can't be taught. It's talent.

Many beginning writers yearn to be told they have "talent" -- because they believe that affirms their self-image, that it means they can become famous for writing.

Not so.

Many of the really REAAALLLYYYY famous writers don't have much talent for writing (for other things, sure, but not the art behind storycraft).

Talent isn't an indispensable ingredient in commericial art. But a sense of what is or is not commercial definitely is indispensable.

Writers or other commercial artists who don't have that sense become victims of agents or business managers rather than fully independent, self-employed businesswomen themselves.

Also, writers who are burdened with talent are always bursting with stories to tell. The real art that a commercial writer needs is to tell the difference between those ideas and develop only the ones with commercial potential.

So, now you've selected an idea and written it out in full, and you take it to a local writer's critique group -- what happens? The different readers all tell you that there's this or that "wrong" with the words you have written.

Here is where you must leap across the dividing line between amateur and professional.

When a critique circle participant (even one who's sold stories already) says "this part really drags. It's so slow, I wanted to put the book down and never pick it up again" -- the amateur writer hears "You are a bad writer, this is all wrong" -- the professional hears "I wanted the story to be about A but in this section it's about B".

The amateur thinks "I have to change this into something that isn't my story."

The professional thinks, "Well, maybe it's not to this reader's taste." or "It's possible to tell not show this information and make it shorter -- maybe leave it out totally -- no, I have a better idea, I'll MOVE IT!" Then the professional thinks, "I wonder how many readers would react that way?" (commercial, remember? Mass audience.) Then the professional interrogates the test reader to find out what story thread they were following that seemed to disappear in the "slow" part.

With enough information about the test reader and enough details about the reader's response to the story, a professional can figure out whether to change anything -- and if so, what to change INTO WHAT.

Making random changes won't help the manuscript sell.

You must make charted changes calculated to take you to a WIDER audience. Your amateur or beginning writer (who is a writer, and a reader, not an EDITOR) can only tell you how their own responses vary. An editor (totally different type of person) can tell you where you have narrowed your potential audience.

So in response to the critique group comment "it drags here" the professional writer might well not change a word of the "dragging" section, but go back and add a character early on in the story -- involve the reader in that character's life and build it in such a way that the information revealed in the "dragging" section, piece by piece, puts that new character in ever growing jeapardy.

Then on rewrite, coming to the dragging section, other changes would get made (cuts most likely -- vivid language -- other tricks of the trade) that would speed up that section.

The beginning writers who put a manuscript before a "critique group" should do so in order to develop the attitude that they are using that group -- not that the group is using them.

If the group is using them to get stories the group finds entertaining, those stories very likely will not entertain the mass market. After all, few people spend their time in critique groups -- lots of people read books.

If the writers are using the group to widen the target audience for their story, then the comments will be viewed in a wholly different light.

And if the professional writer is using the group -- the group does not have to contain a single person who has ever written any fiction, nevermind sold it. After all, readers are the target audience, not writers.

Whether you are a professional or an amateur is not a matter of whether you've ever sold any writing. It is a matter of whether you write to sell.

Jacqueline Lichtenberg

Thanks, Jacqueline! I've seen all that play out in my critique group.

ReplyDelete